Preface: Welcome to the new subscribers who arrived via this very kind blurb in Feed Me. And if anyone is in New York and wants to play poker, respond to this email. I’m eager to play.

I’m listening to Nate Silver’s new book (for free on Spotify if you have premium!), which is pretty good if you’re interested in the stuff Nate Silver is interested in — poker, the political divides in America, and decision making.

The point that has stuck with me most so far comes from a chapter about poker. He describes how modern poker is largely based on “solvers,” which are computer programs that play each other over and over to determine optimal strategy in any given hand. For example, a decision in poker could be: “I’ve been dealt a pair of 10s against two opponents who have more chips than I do. Should I go all-in immediately? Or wait to get more information before betting?”

The computer programs would simulate this scenario against thousands of potential cards your opponents could have and determine the “Game Theory Optimal” strategy: the strategy that maximizes your chances of winning given that the other players are also playing to win.

Silver writes that most people, even professional poker players, are surprised at how aggressively the solvers play. The solvers bluff a lot and put down large bets when they have even a slight edge. In other words, they take on a lot of risk, and that turns out to be the best strategy in these simulations.

When I play poker, I play not to lose. It’s rare that I get to play, and I really like sitting at a table with my friends and feeling the thrill of each hand, and losing means that I have to sit on the sidelines and watch. So I unconsciously try to prolong the game for myself, playing conservatively. Often this means I slowly bleed chips until the end of the game when I’m at a large disadvantage against another player who’s amassed a large stack, and I lose anyway.

Silver is unequivocal in stating that most people do not take on enough risk, not only in poker but in their professional and personal lives.

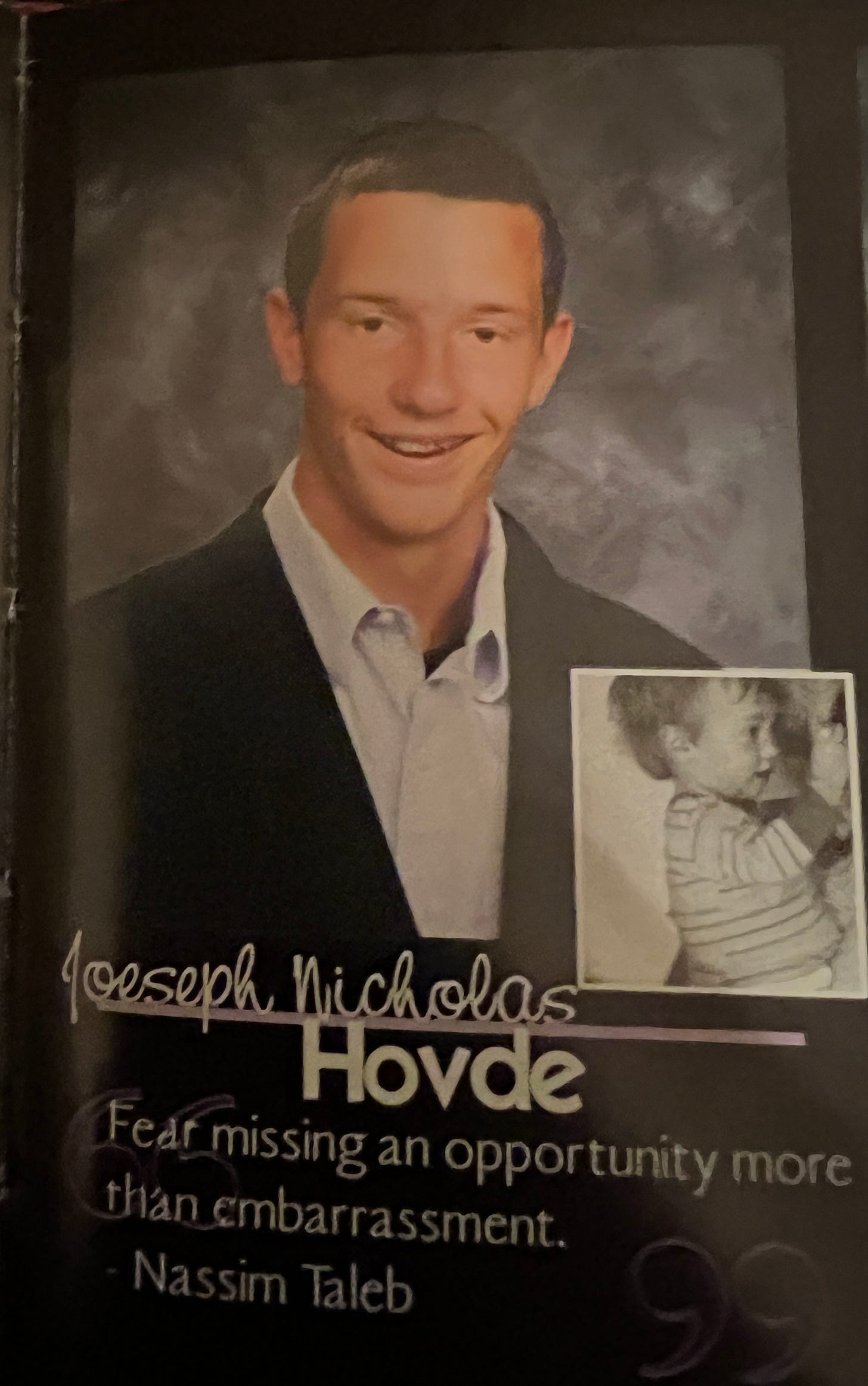

When I heard this I immediately agreed with it. After all, my senior quote in my high school yearbook was “fear missing an opportunity more than embarrassment.” This is, of course, embarrassing on several levels, not least of which is the rather tough picture:

But I haven’t really lived my life in a way I would call “risky,” and so I wanted to step back and think about it. What does risk actually look like, in our day to day lives? Is seizing an opportunity synonymous with taking risk? Is there a way to better differentiate between risks we don’t take enough of and risks we should avoid?

What Silver is saying, and I’m implying in my pretentious yearbook quote, is that people tend to underestimate the expected value of taking at least some types of risks, because they overestimate the negatives (embarrassment, losing all your money etc.) and / or underestimate the positives.

To examine this, below are some risks you could choose to take or not take, along with my simplified interpretation of their expected values.

Implicit in this is some magnitude of utility / disutility I would get in each case. For example, if I expected the rush of successfully shoplifting a bottle of Graza to be the most wonderful feeling a person could experience in this world, I’d probably take the 95% chance that I’d get away with it and shoplift the bottle of Graza; as it stands I don’t weigh that feeling highly enough to do that.

Reviewing the table, the risks that I feel are negative expected value are related to health or morals. The financial, career, and social risks all seemed like good bets to me.

I think that is generalizable, for me at least. I have regretted at least some health-related risks I’ve taken on in my life — not flossing enough when I was younger, drinking too many negronis1. And moral risks have pretty much always felt bad.

On the other hand, I don’t think I’ve regretted taking risks in my life relating to finances or my career or my social life. Moving to new places, taking new jobs, being emotionally open with people — even writing earnest LinkedIn posts!—have never turned out to be things I regretted long term. So, for me, I think I will try to bias myself towards taking more risk in these areas, and trust that I’m overestimating the downsides and underestimating the upsides.

I’m told it’s negroni week; happy negroni week.

lol graza

Love this! I should definitely sit down and think about the decisions I make in life and see where I can take on more risk.

On upside potential, Taleb says that salaried employees almost never get a chance to take advantage of randomness in the world. But a taxi driver sometimes gets a passenger who is willing to pay a crazy amount of money to get somewhere quickly. I think the real life implication for us is - should we quit our jobs and become consultants instead?

Another interesting perspective on risk is that there are nuances to the limits of upside and downside.

For example, health is an area which NEVER has positive shocks, only negative shocks with unlimited downside. You never suddenly get diagnosed with something that increases your lifespan.