The Fall of the Nouveau-Riche University

The declining legibility of prestige in higher education

When I was choosing a college I spent many hours laying on my bedroom floor poring through a thick paperback guidebook. I went deep enough that by the time I applied I had the vague sense that everyone in America had memorized the latest US News and World Report College Rankings and could rattle off the acceptance rates of the NESCACs in order.

I was quickly disabused of this notion after I chose a school and it became evident that most people had never heard of Washington University in St. Louis, and so the fact that I’d decided to go there was basically meaningless for my social standing.

Wash U was a particularly rankings-obsessed school because it was nouveau-riche, having been a respectable local university before becoming much more selective in the 1990s. It had been strategic in climbing up the rankings:

Its application process was easy, requiring no supplements. This increased applications and thus decreased acceptance rate, making the university appear more selective.

The campus was optimized for the college tour. The dining hall was immaculate, the mattresses in the dorms were Tempur-Pedic1, and they have an endowment carveout for the tulips in the quad.

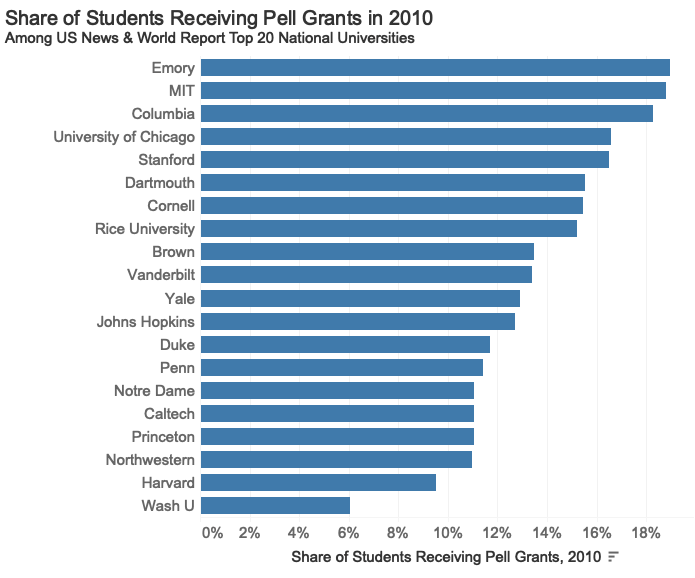

It prioritized growing its endowment and boosting metrics like SAT scores over socioeconomic diversity; this NYT article made a big splash the year I graduated: Only about 6 percent of the freshman class in recent years at Wash. U., as it’s known, have received Pell grants, even though it is one of the country’s 25 richest colleges on a per-student basis.

Pell Grants are government funds awarded to students from families with relatively low household incomes; the data for Wash U the year I matriculated was rather bleak:

Being a student there had a bit of “deal with the devil” feeling — there was a tacit acknowledgement that the school was optimized for growing its prestige, and in turn students would look past the lack of name recognition in the short term or its deep ties to the evil chemical company Monsanto.

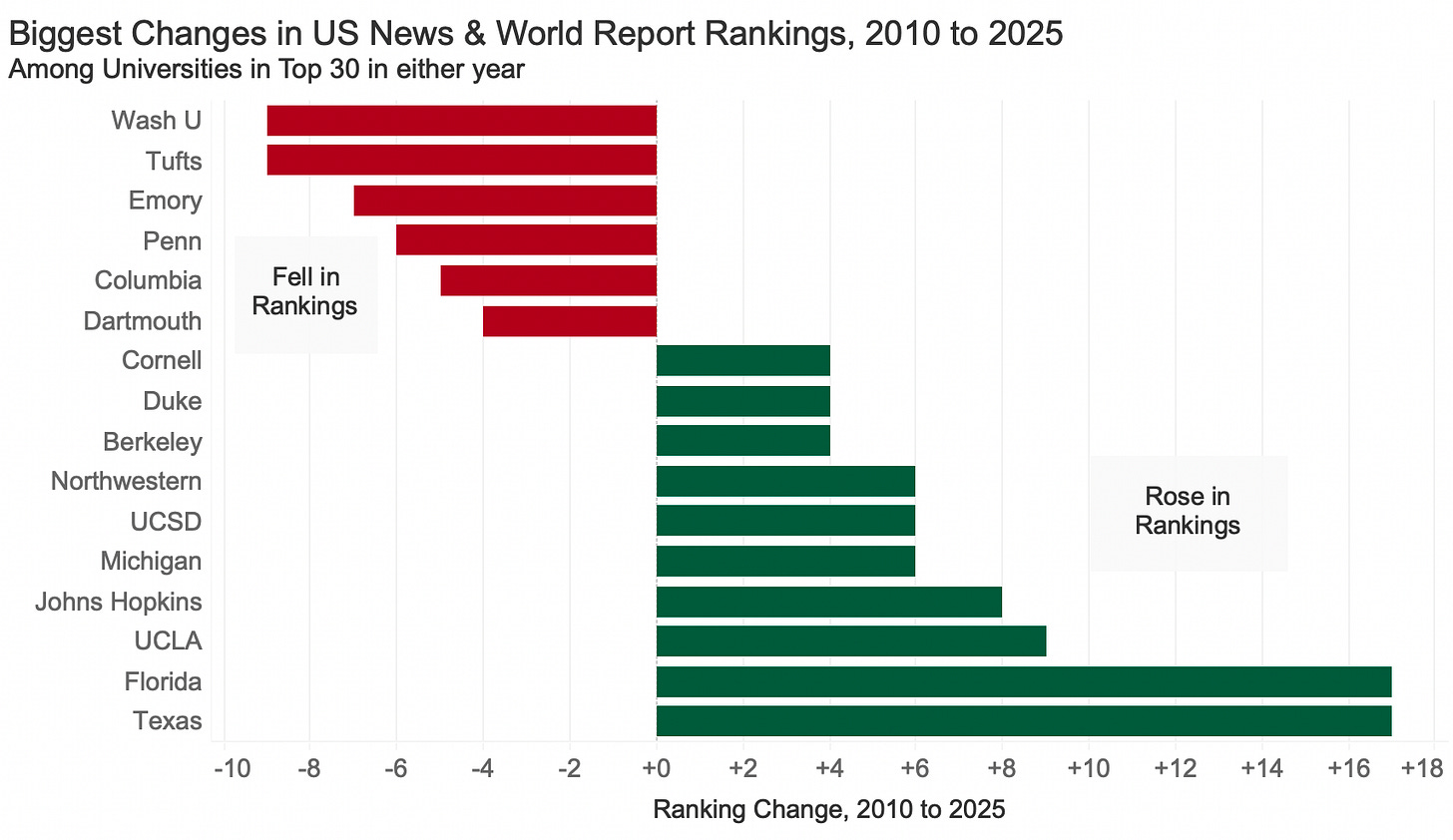

This all makes the school’s performance in the rankings since I went there rather poetic: among top 30 universities, it has fallen the farthest2:

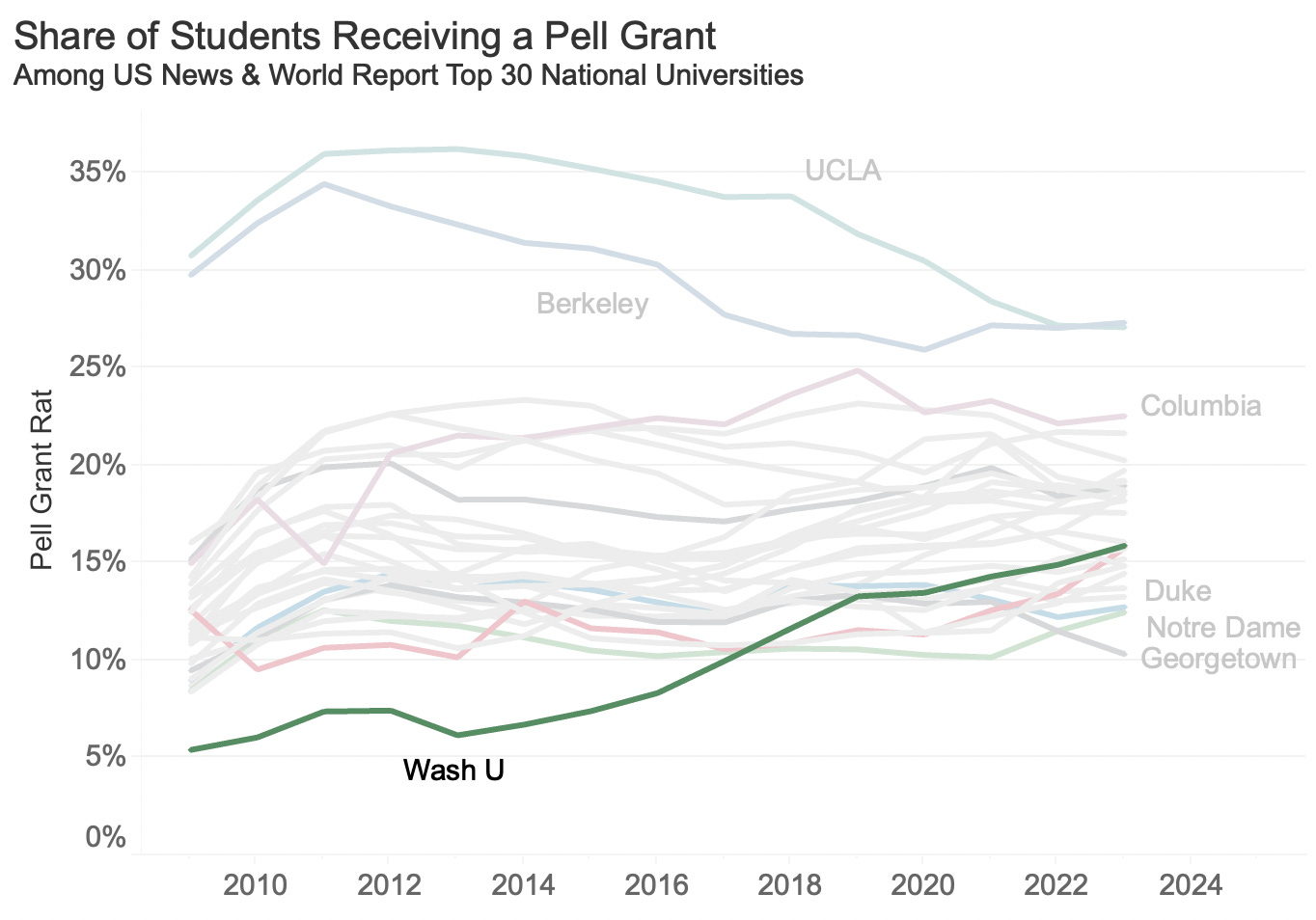

During the late 2010s, the game on the field changed: the US News and World Report adjusted their criteria to more heavily reward socioeconomic diversity (for example, 11% of the weighting is now related to Pell Grant enrollment and graduation) and student debt outcomes. This is a boost to public (and much more fun) universities like the UC system and Texas and Florida, and has hammered Wash U in the rankings, even as it has scrambled to become more socioeconomically diverse:

At the same time, the rankings now put less weight on factors like acceptance rate, class rank, and average class size; this penalized Wash U and other schools that were upwardly mobile in the 2000s in large part because they had optimized for these factors.

This is probably for the best; making higher education more accessible & progressive matters a lot more than having a Source of Truth for College Prestige. But it’s a funny dynamic —it reminds me of rich nations imposing environmental laws on countries with developing economies. Of course the world needs to protect the environment, but it feels unfair that the United States and other rich nations grew rich without caring about the environment at all (just as Dartmouth became prestigious a century before Pell grants even existed!) and are now pushing environmental regulations which will slow growth in poorer countries.

If you read the criteria the US News & World Report uses, you can see how many editorial decisions need to be made to measure something as complex as university quality — for example, they put a 5% weight on borrower debt (each school's typical average accumulated federal loan debt among borrowers only3). The seemingly small detail of measuring debt only among people who borrowed (as opposed to averaging borrowers and non-borrowers together) would have a huge impact on the rankings, because at expensive schools with lots of wealthy students, not many people would emerge with any debt at all, but those who do probably have a lot because of the high sticker price.

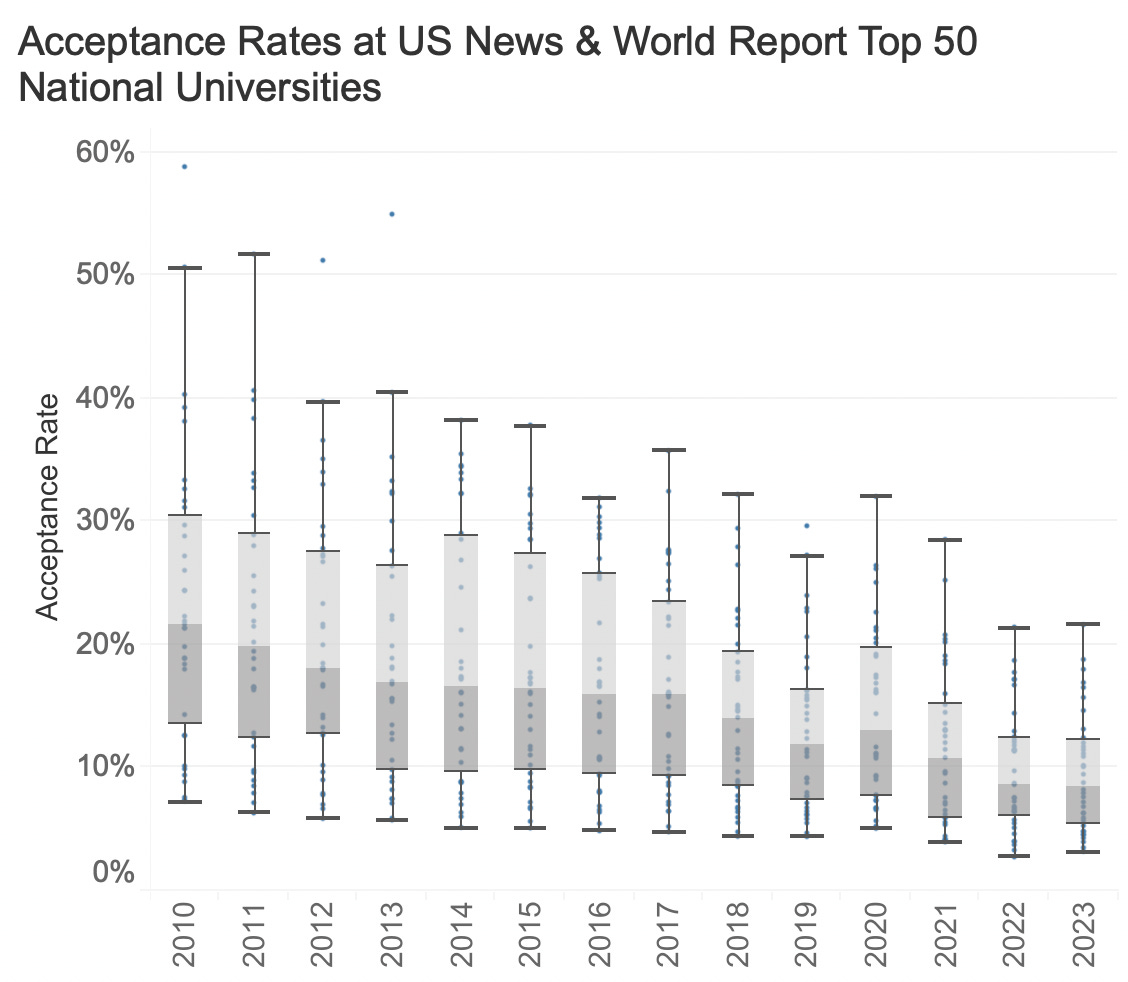

Every college is super selective now

Thankfully I’ve moved on from college rankings to more sophisticated status games (like counting how many people like my posts about Lunch Dr. Pepper) and hadn’t thought about the US News and World Report rankings in years. But I was reminded of them recently in talking to one of our interns, because it is apparently now normal to apply to ~20 colleges; when I was applying it seemed rare that anyone applied to more than 5 or 6.

This leads to a prisoner’s dilemma, where it is rational for each individual to cast a wide net, apply to many schools and see the best place they get into. But then as acceptance rates fall, everyone must do more work just to keep up4. It’s also tough for the schools, who have a much harder time “qualifying” the applicants’ interest; if there’s only a small chance that an accepted student chooses to attend it seems tricky to manage the size of the incoming class.

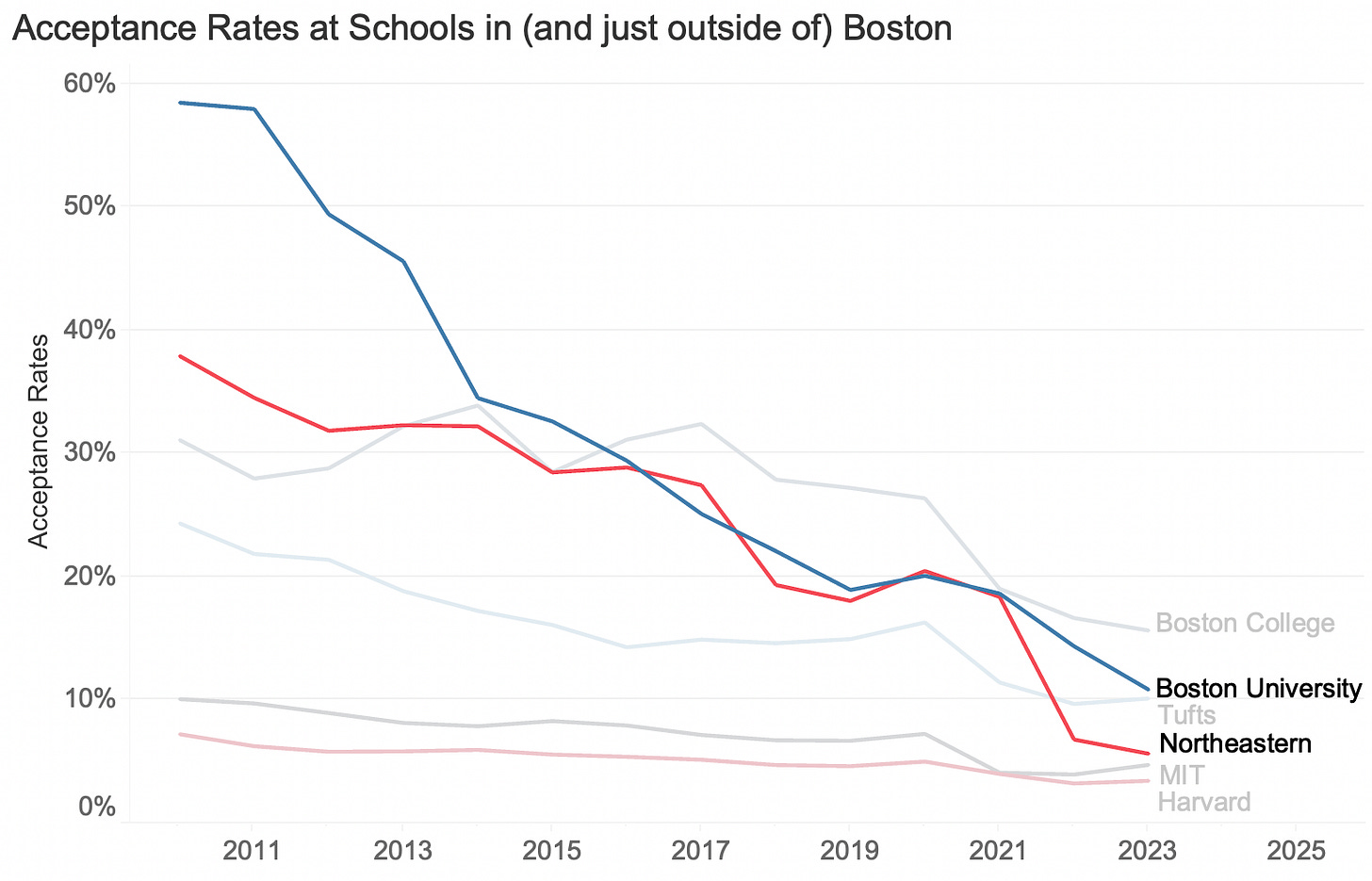

This has led to some wacky outcomes, as top schools have all gotten more selective:

This includes particularly dramatic plunges in acceptance rates at both BU and Northeastern, who appear to be engaging in some prestige-optimization of their own:

This brings up an interesting point: as every school gets more selective, and rankings pivot to measure social impact, prestige signals are much less obvious. It used to be that if someone said they went to school “in the Boston area” with a soft smirk, there wasn’t a lot of ambiguity. Today, with its 6% acceptance rate, they might be alluding to Northeastern; how am I meant to know?

We seem to have a sort of “prestige-signaling vacuum” in higher education. It makes me think that universities will have to more actively brand themselves; I am anxiously awaiting whether the Wash U board takes my suggestion for season 4 and comes over the top with an offer HBO can’t refuse:

Thanks for reading! Check out

’s latest consumer trends report for lots of interesting survey data on the state of consumer and their feelings towards longevity, AI, and podcasts. The AI stuff was somewhat comforting in that most people are much more optimistic about it than I am.I enjoyed this interview with angel investor & recently appointed Meta boardmember Charlie Songhurst, whose LinkedIn presence is deeply aspirational in its brevity:

Songhurst asks CEOs of the companies he invests in the below question. I can’t resist a little pseudopsychological profiling so I’ll pose this to you now, and share my ranking and the results next week.

In retrospect this was both completely absurd and also money well-spent. I remember getting back from my tour of Wash U and being wowed by the mattresses; a couple hundred dollars of foam is a low customer acquisition cost when the LTV is in the 6 figures

Along with, incidentally, Tufts, where my girlfriend and many of her friends went. Yikes!

I’ve become much less trusting of statistics like this since I started working on similar ones professionally; there are in fact many answers to “which college has the highest average borrower debt?”

This reminds me of the internet’s impact on the labor market. Has the internet made it easier to find a job? In some ways, sure. But the decreased friction has made it a harder matching problem for both job seekers and companies, because there are so many more applications to select from — both sides are forced to consider many more options.

Very interesting.

Seventy-eight years ago it was much simpler. I made a single application, to Purdue university. The tuition was $50/semester ($725 in today's dollars); Purdue had an extension in my home town, making board and room much cheaper; the public library was a good place to study; and it and the school were within easy walking distance.

I do not envy today's HS graduates or their parents.

I hate the discourse on undergraduate university selection. It's all based on meaningless rankings rather than the things that matter. The value of your degree is based on the strength of the program you studied under and the name recognition of your major professors who are going to write you letters of recommendation. Studying at a big-name school that has nobody expert in your field is a terrible decision (though the Ivies try really hard to cover everything). And studying at a state school under an up-and-coming professor who gets hired away to teach at Harvard or Yale is a great way to not pay the latter's prices. But all this depends on knowing your major early on, educating yourself on who's important within the field, and making strategic choices.