Where did Tiger Global Go Wrong?

Revisiting a disruptive VC strategy

I remember this excellent post by Everett Randle being passed around in the spring of 2021, analyzing Tiger Global’s disruptive new strategy for investing into startups. It was just two and a half years ago, but the world looked very different. Your friends were pretending to be hospitality workers to get early Covid vaccines, people were flipping NFTs and moving to Miami, and venture capital markets were hot.

I was working as a data analyst at a venture fund at the time and heard investors talking about Tiger’s investment style. The perspective I formed was this:

Tiger Global is a storied hedge fund and an outsider in Silicon Valley tech. They developed their reputation by investing in public markets, but as early-stage tech valuations soared and tech companies stayed private longer they started to invest at earlier and earlier stages

Tiger was willing to pay extremely high valuations, which annoyed more price-sensitive investors. There was a perception that they were pushing up the prices irrationally and causing a bubble.

Tiger outsourced most of their investment diligence to Bain, and they did deals extremely fast. While a traditional VC might spend 3 weeks to a month kicking the tires of a potential investment, Tiger would get deals done in a weekend.

In a world where most venture firms try to differentiate by convincing founders that they will be able to add value to their company, Tiger didn’t pretend. They didn’t demand board seats in the startups they invested in, and they promised to get out of founders’ way after they wired them the money.

Randle summarizes Tiger’s new approach nicely in his article (emphasis mine):

Tiger has introduced a new play style centered around velocity to disrupt the market and exploit their competition’s tendency to cling onto stale rules/norms.

To me, it seemed like Tiger was taking a ton of cash and buying an index fund of early-stage tech: that is, a large, diversified basket of companies. And this seemed brilliant! Tiger’s style seemed analogous to early Vanguard in the public markets: a low-cost model where you could own a slice of a growing market. Sure, you wouldn’t have outsized returns, but that is mostly luck anyway and you could deploy a ton of money into this strategy because it moves so fast and it scales. Instead of paying a bunch of HBS grads to debate one another about the merits of a company for a month and then fly business class to board meetings for years, you can simply invest way more money into lots of companies quickly and then let them alone to grow.

This looked great in a world where valuations always went up. And, if you believed that “software is eating the world,” that didn’t seem unnatural: this new sector of the economy should have been growing rapidly. It was a race to own a piece of it.

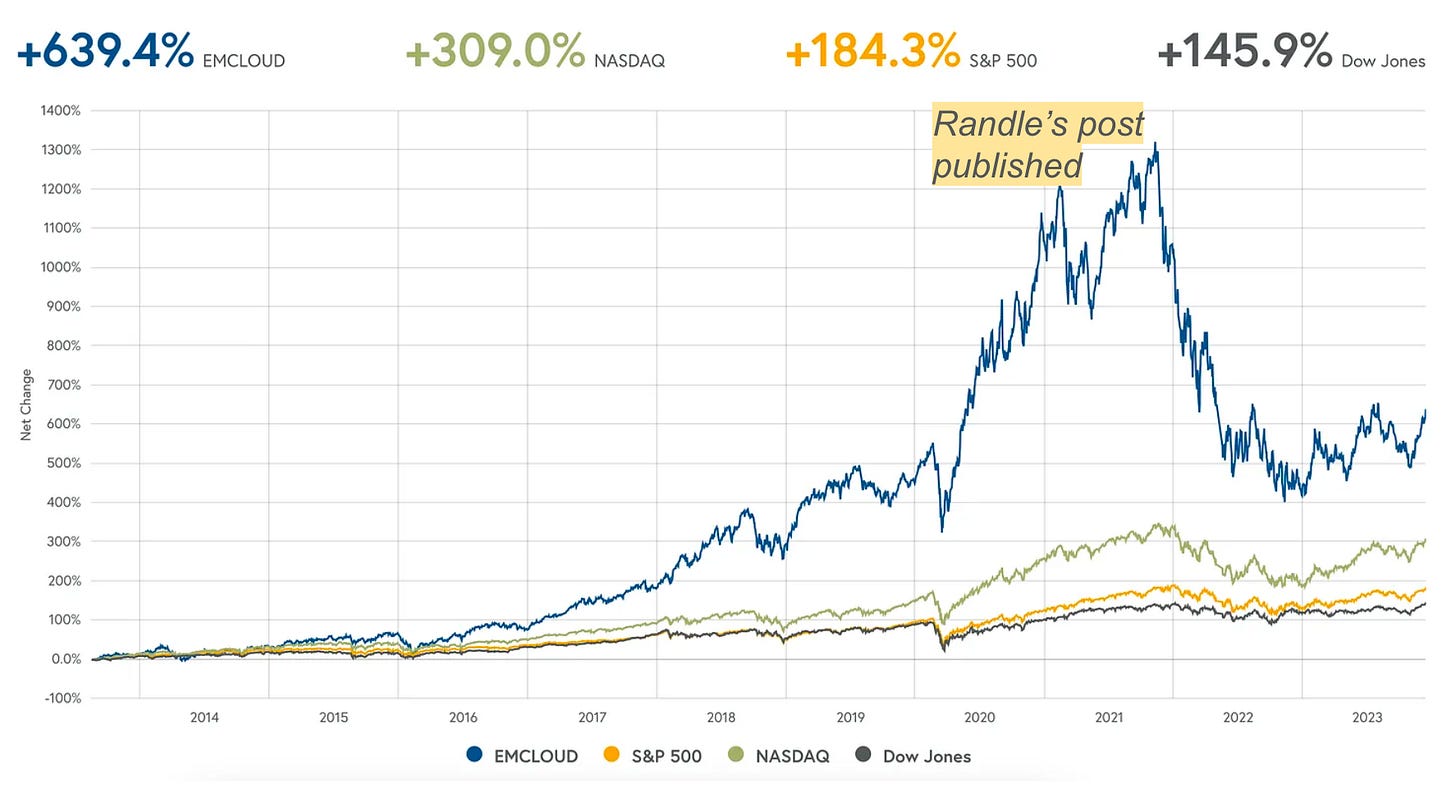

Of course, the party ended. Interest rates are up, the NFT market collapsed and the tech people are moving back from Miami. Randle’s piece was published when the Bessemer Cloud Index (below, a rough public proxy for late-stage private tech markets) was near its peak. Today, Tiger’s portfolio is way down and two of its private markets leaders have left the firm.

So, what went wrong with Tiger’s venture strategy? Let’s look at the flywheel that Randle assumes for Tiger’s VC Investments:

As of today, in late 2023, it is safe to say the dollar returns at the center of the flywheel have not been good. We can examine the specifics driving that to better understand what went wrong.

Issues with Investment Velocity

The flywheel assumes that higher investment velocity leads to more investments and a more diversified portfolio, which makes each investment less risky and allows for higher expected returns.

Tiger was able to deploy money quickly into lots of companies, but that did not protect them from a large blowup because their timing was very bad. They picked an awful time to invest billions of dollars into private tech companies. Interestingly, the speed with which they deployed capital (their “Velocity”) matters a lot here because it magnified their mistake in market timing. They were able to put billions of dollars into companies at the market peak, whereas most funds’ investment processes simply wouldn’t allow this to happen.

So, Tiger was able to quickly invest into a lot of companies and be diversified in that way, but that strategy left them very exposed to market timing risk. And the market itself blew up, so the prices that Tiger paid mostly look terrible now.

In this way, the slower pace that more traditional venture firms take to deploy capital is a feature, not a bug: it lets them dollar-cost average into the market, investing at different points in the cycle.

Issues with Higher Valuations

According to the flywheel, Tiger’s velocity allowed it to accept a lower projected rate of return on each investment (because it could invest so quickly that it could make up for it in volume and return more cash in a given time period). This let Tiger set higher valuations for companies which helped them win competitive deals.

I would argue that on balance, valuations as high as they were this cycle are not a better product for founders and actually make the companies less likely to succeed than lower ones, and so this is not a virtuous part of the flywheel. It seems like sky-high valuations and too much cash encourage companies to get complacent, to overhire, and then to spiral when conditions turn against them. So I think the cycle looks something like: Tiger pays high valuations —> Eager founders take the high valuations —> These companies are a bit less likely to succeed than they would have been at a lower valuation.

But, I expect this isn’t a huge driver in returns and Tiger’s ability to use price to win deals helps them more than it hurts them, all thing equal. I think this phenomenon probably only holds during manic points in the market; in more normal markets it seems like Tiger’s ability to pay higher prices would benefit both Tiger and their portfolio companies.

Issues with “Low-Touch Capital”

It is easy to see why Tiger’s offering would be attractive to founders. It’s a lot of work to raise money and it distracts from actually building the company. And investor board members don’t necessarily help the company and can even harm it. So, an investor that will give you a lot of cash quickly and then get out of the way is appealing.

A more complicated question is, did doing less diligence make Tiger’s investment decisions meaningfully worse?

Tiger definitely made some bets that look foolish in hindsight. They put $39m into FTX, which obviously could’ve benefited from more skeptical diligence. But…lots of the best traditional VCs did that too.

Tiger has had to mark down investments in web3 companies like BAYC and OpenSea, which seem like they were driven by mania and not sober long-term thinking. But again, many VCs at the most prestigious firms made similar mistakes — did the outsourced / abbreviated diligence actually cause these mistakes? Hard to say.

I think the verdict is a bit more mixed here. I don’t have much faith in most VCs to either accurately predict which companies will succeed or to do very much to help companies succeed after investing. So even though Tiger had some big misses, I don’t attribute most of that to their low-touch investment processes. In my view, Tiger was throwing darts very quickly while most other VCs were taking their time to intellectualize investment decisions that probably weren’t much better anyway.

Here’s how I’d sum up Tiger’s approach, with the benefit of hindsight over the boom and bust of the bast few years:

Their high-velocity approach magnified their mistake in market timing and left them hugely exposed when markets crashed

The strategy of accepting lower returns and making up for it with scale and speed still makes sense to me and I don’t think their struggles invalidate it.

They made some investment decisions that seem like they could have been improved with better diligence (FTX most notably), but so did many other investors following traditional venture practices.

To me, it feels like this strategy should work on a really long time horizon (some sort of permanent capital where you can continually invest and don’t need to worry so much about timing of your returns). But, that is a rare setup and I’d imagine it will now be much harder for funds to try something similar given what’s happened with Tiger the past few years.

Thanks for reading! Reach out or comment with any thoughts.

Great post. Like many others Tiger put money into the market during the ZIRP era, when valuations were rising inexorably and of course Tiger and competing capital allocators felt pretty good about taking credit for the portfolio gains from their brilliant strategies.

From personal experience, we went up against one or two "Tigers" who competed with us for coveted companies that were for sale during the later stages of ZIRP. These people had done well investing hyper aggressively during early ZIRP, and by mid-late ZIRP they were formidable adversaries in competitive bids. We lost one and we won one. We made several X on the one we won...time will tell whether we would've made money on the one we lost.

Lee Fixel from Tiger was one of the first mega early stage investors in Indian Tech (Flipkart, Ola etc.). The inside joke is that he would fund any idea as long as the founder is from traditional business castes (baniyas etc.) who went IITs with a double digit JEE rank. A crude American equivalent would be like funding only Jews who went to Stanford. All the social politics aside, is actually a fairly good proxy and they ended up being quite successful.