The 1 Big Thing I've Learned from Data Analysis

Who runs the world?

This tweet articulates an implication of the most important concept I’ve taken away from my career so far working in data analysis:

Analyzing data, I am constantly surprised at how often the vast majority of the members of a population hover around some small median value, and a very small number of outliers have much, much higher values.

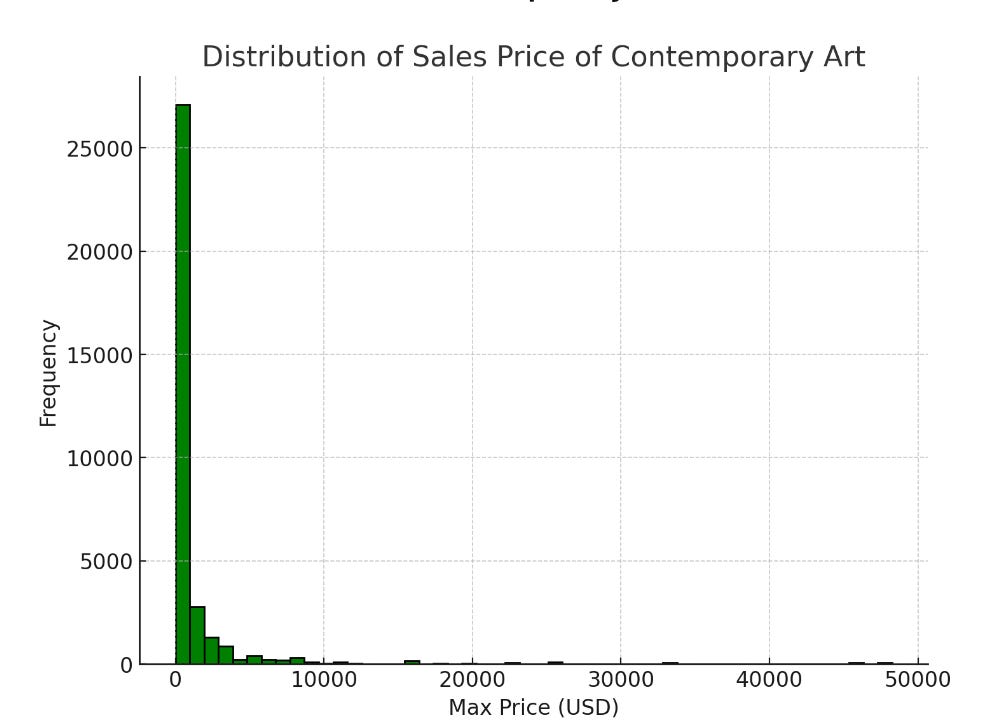

In other words, the distribution has a long right tail, and looks something like this:

This is the distribution of transaction prices in a dataset on art sales I found. Most of the works of art were sold for a relatively small sum, under 1 thousand dollars or so. The median sale price in the dataset is $200. But a very small number sold for $10,000 or more, and a few extreme outliers are up around $50k, or ~250x the median.

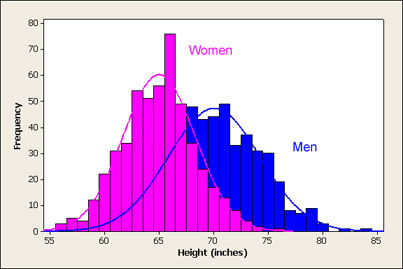

This distribution is in stark contrast to the normal distribution, which was the focus of my statistics classes and I find a lot more intuitive. The normal distribution does a good job modeling many physical phenomena, for example heights:

But over my time working with data, it’s been exceedingly rare that I plot the distribution of a variable and it looks like a bell curve. It is much more common that it looks something like the heavily right-skewed distribution of sales of contemporary art.

I think many people realize this intellectually and cite things like “The 80/20 rule” or “power laws” to explain it. But I don’t think most people properly internalize just how common or how extremely heavily skewed these distributions are — I know I didn’t, and it’s taken years of making charts like this for me to start to expect them.

As another example, we can plot Wikipedia pages with the most views on a random day in 2019. It looks like an Avengers movie had just come out; the list is kind of embarrassing for the world. At the very top end, Avengers_Endgame had 2 million pageviews that day:

So, those are the pages at the very top, or the very far right edge of the distribution. But Wikipedia’s page views are extremely right-tailed, and we can see this if we count the number of pages at each order of magnitude of popularity:

The vast majority of pages on Wikipedia are clustered under 100 views. But then there are a very small number of pages that get many thousands times that. It forms a sort of reverse pyramid, where as you move down you get to a new stratosphere of reach and there are many fewer pages.

This brings us back to the original tweet, and something that I’ve come to believe much more viscerally about society: “The more influential you go, the smaller the circle, and the more everyone knows each other.”

It feels a little funny writing it, it sounds a bit cloak-and-dagger and almost conspiratorial, but I think that power in society looks a lot like these heavily right-skewed distributions. And so at the very top, there are only a handful of people, many of whom know each other, who hold a huge amount of influence.

This is clearly true with money — most US households’ net worths are clustered well below $1M, but there are a few hundred billionaires at the right tail of the distribution. Power and influence seem similar — partly because power and money can be exchanged, and partly because power seems like it compounds in a similar way to money.

To compare societal power directly to the distribution of Wikipedia views, a very crude inverted pyramid of how I perceive power in the US might look something like this:

~200 million marginalized people without much money or power to speak of

~100 million middle class people with enough money & power to have control over the lives of their family

~10 million upper-middle class people; the “managerial class” who have power over their own lives and their immediate communities.

~500k people people whose families might have their weddings announced in the New York Times, but they still have LinkedIn accounts that they manage. They have regional power.

10k people who are hundred-millionaires / luminaries; call it the Malcolm Gladwell / Marissa Mayer tier. This group gets called on to do commencement speeches, sit on boards of Fortune 500s, write big checks to charities and political causes. They have limited national power.

1k celebrities, big-time politicians, and billionaires who go to the Met Gala and / or Davos. Call it the Lina Khan / Jay-Z / Peter Thiel tier. They’re tightly socially intertwined with the tier above, rarely interact with people outside their social strata, and have national power and sometimes international power.

10-50 people with the power to change the world relatively quickly and unilaterally. Presidents, a select group of CEOs, and a few entertainers (Zuckerberg, Obama, Trump, Harris, Taylor Swift come to mind in this tier). They have a lot of national power and at least some level of international power.

In this system, you might get George Clooney calling up Barack Obama and Nancy Pelosi and, with a heavy heart, letting them know that they need to get Biden off the ticket (and Clooney probably met Obama through Bruce Springsteen when they were sipping tequila at a benefit for one of Oprah’s charities; Sun Valley in August, you can’t beat it).

Or, you might have Jack Dorsey agreeing to sell Twitter to Elon Musk, because there are only a handful of potential buyers that Jack views as powerful enough to take over the company.

Or Taylor Swift and Kanye West feuding because they’re 2 of ~5 entertainers in their stratosphere of influence, and they both want to stay there.

It’s disheartening, because this structure it makes me see the world in less democratic terms. It feels like there are smoke-filled rooms in the Skull & Bones club and on Wall Street and on private yachts the world over where decisions about all our lives are being made. I would like to believe that it is easier to move up these rungs of power in the US than, say, 1770s France, but that doesn’t make me feel much better. It seems like this type of distribution just tends to emerge in lots of systems, and in societies that means a small, interwoven group of actors who have a hugely outsized ability to do things in the world.

If you haven’t read any of Nassim Taleb’s books, his career is built around this principle. I recommend Antifragile first. Don’t take it all too seriously, unless you already know what you’re doing.

The post reads like someone who just found him.

Another observation - if you took the top 100 wealthy guys and put them in a room, the 100th wealthiest guy is so way off from the top guy that these two can realistically neither relate nor compete. But to the outside worlds they are both 'top 100'. No other set of 100 except the top set has this problem.

A parallel is to elite universities - if you look at the students taking Math 101 in MIT, the bottom half of the class, no matter what they do, has no chance in hell of competing with the top half. This is not true in an almost other Universities. If you put in the work, you have a realistic chance of topping the class. Not being able to compete in your own class is big psychological burden (no matter how good you are, nationally). I think Malcolm Gladwell talks about this in one of this books. I experienced this first hand.